My last post about the navigational Heiau called Ko’a Holomoana in Hawaii made me notice another megalith that could be described as “navigational”. Although the scale of the map it appears to refer to is not as wide as the Pacific Ocean, it nonetheless describes a large area.

In this post, I will be making a case for “Les Menhirs de Lutry” as a geographical alignment. This megalith is made up of large and not so large stones on the shore of Lake Geneva (or Lac Léman, which is how it is called in the area, a name that dates from the Romans – ‘Lacus Lemannus’ – from a couple of thousand years ago). As I understand, no one has ever published this interpretation, but it seems to be an oversight, and should at least be contemplated as an explanation of its unique layout.

Megaliths come in many shapes and forms, and their interpretations are a part of guesswork and careful investigation of their geographic situations. There are two main categories that often overlap: they can be ceremonial, such as for a burial or place of ritual; and/or cosmological in their intent, meaning they are astronomical alignments which are in use as a calendar where the heliacal rising and setting of stars is marked, and allows for the study of the motion of planets, stars, the Sun and our Moon.

The finding of the navigational Heiau in Hawaii, and now the possible representation of this alignment of stones in the town of Lutry might elude to a third category, which could be named “geographical” or geodetic.

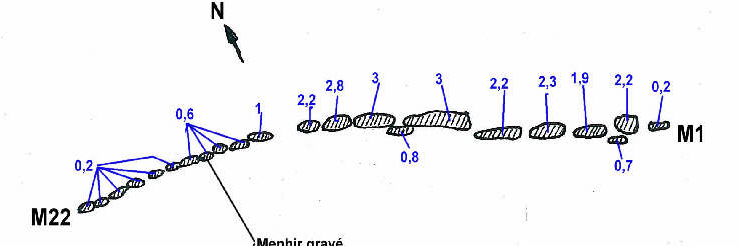

Full disclaimer: obviously, I am not trained as an archeologist. I am just curious about astronomical alignments that megaliths often demonstrate. This kind of cosmological stone construction is most often found in two typical layouts: rings or circles (like Stonehenge in England), or straight lines which are often parallel (like Karnak in Normandy). The stones in Lutry are loosely aligned with the summer and winter solstice, but their alignment falls in between the two typical layouts – the Lutry megalith stones are placed in a row; but at some point they bend to the south, as you can see in the image below:

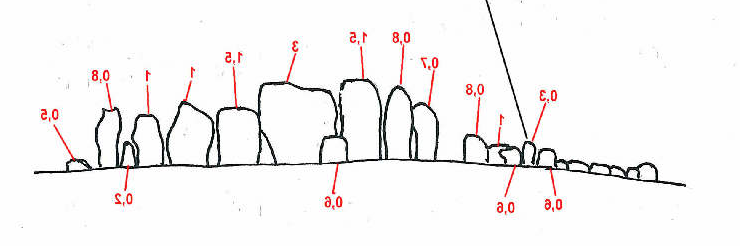

Secondly, there is a vertical progression, as the eastern part is composed of larger and taller stones that progressively get smaller as it moves to the west and starts bending to the south, as shown in the next image:

The alignment is on the shore of Lac Léman, and across this body of water, a large massif of Prealps mountains dominate the horizon. Unfortunately, due to the fact that the monument sits in the middle of a small town, this imposing view is obscured by houses and therefore separates the geographical features that these stones are representing. In order to recreate the original setting, I scanned the alignment and placed it in plain view of the landscape as it would have been originally. I removed the houses and placed the monument as it would have looked when it was built:

Each stone matches a large mountain block, and as the mountains recede, the stones get smaller. There are two stones that must have been lost through time. When we take a different view from above, there is more that matches the geography. As we see in the plan above, the stones bend to the south as they get smaller. This replicates quite accurately the natural bend along the south shore of the lake as it it moves to the west. To highlight this, I have highly magnified the stones to show how accurately they match the curve of the lake.

Here is another view from the south

These two montages highlight the close match between the alignment of the stones with the shoreline of the lake. The combination of the silhouette view of the mountains as shown in the first montage with the stones matching the curvature of the shoreline shown from above in the second and third, reinforces the theory of intentional map making.

The question then arises: why would the builders of this megalith need to build such a representation of the mountains and lake shore on their side of the lake? Obviously, we don’t know; so I ask myself, why do we use maps at all? Especially such a large map that obviously we cannot fold and transport in our backpack? These kinds of maps are used in situations (i.e. situation room) where we need to plan some kind of collective action: hunt, prepare for war, celebrations, exploration – where you want to coordinate and plan the movement of a number of people.

It could also be that these mountains and this lake have mythical meaning to the megalith builders, and to recreate it in a more manageable scale, it allows them to have some control over the elements. The alignment seems to not have any particular astronomical alignment – it does not face east or west, where most celestial movements occur and are more obvious.

So, is geographical mapping a category for these megalithic structures? I first experienced one, as I mentioned above, when visiting the navigational Heiau on the Island of Hawaii, a megalith that maps the major islands of the Pacific Ocean. It seems to me that Les Menhirs de Lutry appear to follow that pattern. If this theory holds, it shows that the builders of these ‘geographical megaliths’ had some impressive geodetic knowledge and abilities.