In the heart of California’s Carrizo Plain National Monument, an ancient natural formation known as Painted Rock stands as a testament to the region’s rich cultural and ecological history. For centuries, the Chumash people painted many petroglyphs on it inside walls and regarded this site as a sacred place, using it for ceremonies, initiations, and astronomical observations. Recent observations reveal an extraordinary feature of Painted Rock: its alignment with key celestial events, echoing the cosmology of the Chumash in remarkable ways.

The Chumash were a highly advanced and vibrant society whose territory stretched from Malibu Beach in the south to the central regions of San Luis Obispo County in the north, bordered by the Carrizo Plain and Mount Piños to the east (the highest peak in the region at 8,831 feet), and the Channel Islands to the west. Archaeological evidence shows that the Chumash settled in the Carrizo Plain as early as 2000 BCE, with their population peaking around 1000 CE. However, the population diminished steeply after that, likely due to significant climate changes that affected the region’s resources, Some Peoples from the Yokuts settled and shared the area until the 19th century.

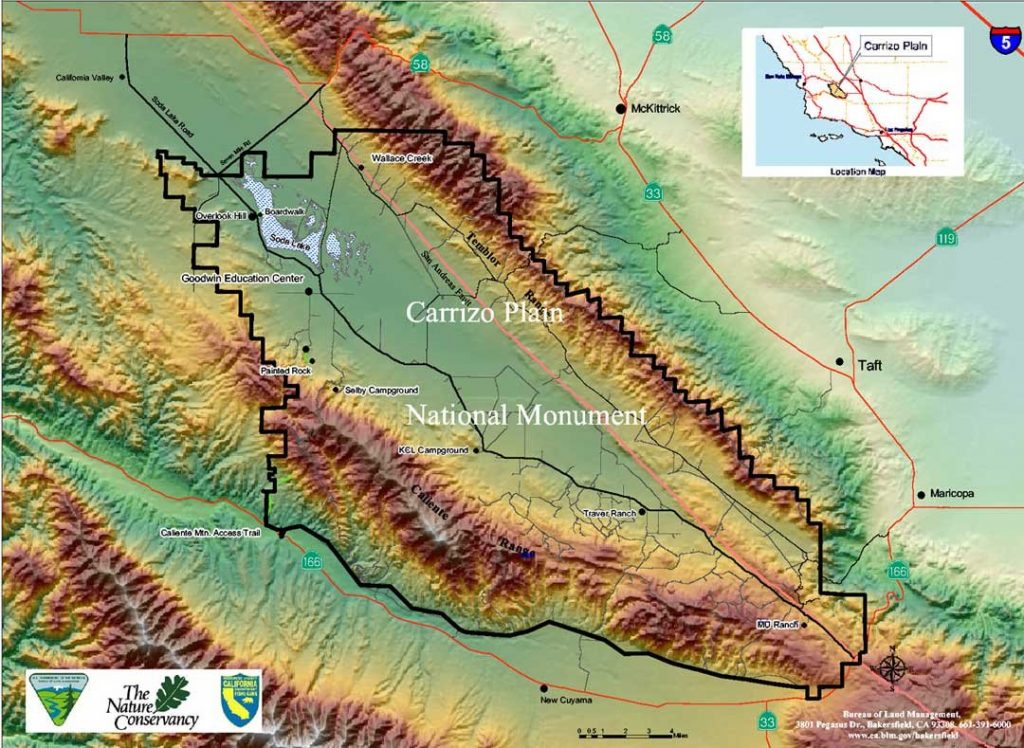

The Carrizo Plain is bordered on the east by the San Andreas Fault, a geographical feature that not only shaped the landscape but also influenced the water sources and ecosystems the Chumash depended upon. Painted Rock, located near the heart of the plain, became a spiritual and cultural focal point for the Chumash people.

Chumash cosmology divided the universe into three interconnected realms: the underworld, the middle world, and the sky world. Humans inhabited the middle world and were tasked with maintaining balance between the realms, which were permeated by a neutral energy. Unlike many cultures that revered the Sun, the Chumash held the North Star (Polaris) as the most significant celestial object, symbolizing stability and balance in the universe.

“California’s Chumash Indians thought of the sky gods this way. They saw a balance of nature and the world order in terms of a nightly gambling game played between two teams. Sun was the captain of one team, while the pole star, Polaris, led the other. Polaris was known as Sky Coyote, and its pivotal position among the stars made it a symbol of the night.

For a full year they played, and at the winter solstice the score was tallied. Moon, that expert at counting out the days, kept score. If, at the winter solstice, Sun was the winner, it would go bad for people on earth: rather than return upon his yearly journey back to the north, he might just continue on south and leave the earth in the dead of winter, with the cosmos out of balance. Sky Coyote was a benefactor, a benevolent influence. If his team won, the order of things would be restored.” E.C. Krupp Echoes of the Ancient Skies

My wife, Sarah Pillow, and I have been visiting the Carrizo Plain for many years, drawn by its unspoiled landscapes, pristine night skies, and rich history. Our connection to the area deepened through stargazing and learning about the indigenous Chumash culture, so vividly demonstrated at the Painted Rock monument. As an amateur astronomer with a passion for sky lore and archeo-astronomy, I was particularly intrigued by how the Chumash integrated celestial events into their cultural practices.

In August 2023, I conducted a detailed scan of the interior of Painted Rock using an iPhone and the Scaniverse app. The scan data was assembled in Blender, and I also created a 360˚ panoramic photo of the site, which I inserted into the Stellarium app for astronomical analysis. The results were striking: the rock formation, shaped like a large horseshoe, has its opening perfectly oriented towards Polaris, a celestial body of profound significance in Chumash cosmology. (see below a short video that show the North view of a whole year motion of the constelation around Polaris)

Another remarkable discovery emerged during my analysis: on the south side of Painted Rock, the Sun at noon during the winter solstice aligns precisely with the top of the formation. This natural alignment mirrors the Chumash’s understanding of celestial cycles, which informed their rituals and worldview. (see below a short video of the Sun, during a whole year at noon, looking south from inside the rock)

What makes this discovery particularly fascinating is that Painted Rock is a natural formation, not a human-made structure. Its alignment with these celestial events appears to be a fortuitous occurrence, yet it seamlessly supports the Chumash belief system. It highlights the deep connection the Chumash people saw between their sacred geography and the cosmos.

Tragically, the Chumash population was devastated during colonization. The establishment of Spanish missions introduced disease, forced labor, and cultural disruption, and westward expansion by settlers led to further extermination of their population and heritage. Yet, the Chumash legacy endures through their artifacts, traditions, and the profound cosmological insights that continue to inspire and amaze.

The Carrizo Plain is more than just the home of Painted Rock. It is a vital ecological and cultural preserve, with vibrant wildflower blooms, rare wildlife, and one of California’s last native grasslands. Its dark, unpolluted skies make it an ideal destination for stargazers and those seeking to connect with the celestial traditions of the past.

I hope this discovery inspires further exploration of Painted Rock and its connections to the Chumash worldview. By uncovering and honoring the interplay between culture, nature, and astronomy, we can better appreciate the profound legacy of the Chumash and their relationship with the universe. If you are fortunate enough to visit the Carrizo Plain, approach Painted Rock with reverence, keeping in mind its cultural and spiritual significance. Together, we can ensure this sacred site remains a source of wonder and learning for generations to come.