How do different cultures hear consonances; what are the facts that affect our perceptions and how might a word we use change if it is spoken or sung?

Is the way we hear and sing music unique to all ethnicities? And why, as we become aware by listening to music from around the world, do these differences and similarities arise? What follows is a summarization of two studies on this topic.

1. Communalities (consonances)

In the first study, the art of music is universal: comparative studies made on the subject show that there are underlining patterns that exist across cultures. In almost all of them, we find that the pitch of spoken and sung words have several different behaviors. For example, sung words are produced at a higher pitch; the pace of the word is slower; and the pitch is more stable than when the words are spoken.

In a paper on anthropology in Science Advances, the author put these facts to the test:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adm9797

Concerning the pitch of a word, the article states: “we realized that in speech we recognize phonemes by the shape of formants (formants are an analysis of the component frequencies that make up human speech). These formants characterize how upper harmonics’ content is emphasized or attenuated. In speech, the frequency content that is conveying information is not fundamental frequency but harmonics; whereas in music, it is the lower fundamental frequencies that contain the crucial melodic content. We speculate that the difference in emphasis on formants versus fundamental frequency may underlie the difference in pitch height between speech and music we have identified.”

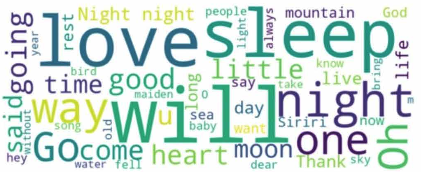

The “use of longer acoustic phrases, greater sound pressure, and less noisy sounds may ease the intelligibility of pitch information. This increased loudness and salience might also support evolutionary propositions that music evolved as a mnemonic device or as a night-time, long-distance communication device. The lyrics of the chosen songs [of the study] frequently mention “night,” “moon,” “sleep,” and “love,” which may further support the nocturnal hypothesis.”

To recapitulate features that the study identified as differentiating music and speech along a musi-linguistic continuum are pitch height, temporal rate, and pitch stability.

Since utilization of pitch can also be found in language (e.g., tonal languages: increasing the pitch of the final word in an interrogative sentence in today’s English and Japanese), inclusively probing what we can communicate with pitch in human acoustic communication may give insights into the fundamental nature of songs.

Meanwhile, the features identified as shared between speech and song—particularly timbral brightness and pitch interval size— represent promising candidates for understanding the role of vocalization that may shape the cultural evolution of music and language. Together, these cross-cultural similarities and differences may help shed light on the cultural and biological evolution of two systems that make us human: music and language.

2. Differences (dissonances)

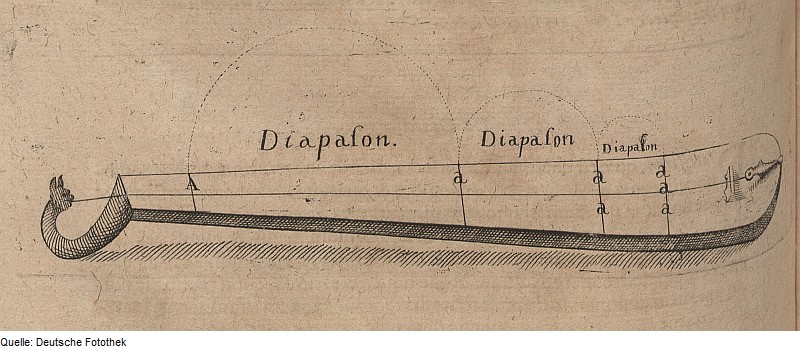

The debate about following perfect mathematical rules, which was supported by all the followers of the strict tuning rules established by Pythagoras and based on the natural harmonic series, started to be questioned by the end of the Renaissance. The musicians of the time became more inclined to follow their ears and bend the strict rules to attain smoother relationships between the notes of the scale. In any case, these strict rules were never completely followed, as is clear when listening and comparing Western to Chinese and South Asian music. This study is addressing how these different tunings came to be used around the world.

The complete article: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-45812-z

This study explored harmonic relationships that are pleasant or unpleasant to our ears by having participants listen to “dyads” (two-note intervals) in which the sounds were manipulated in several ways.

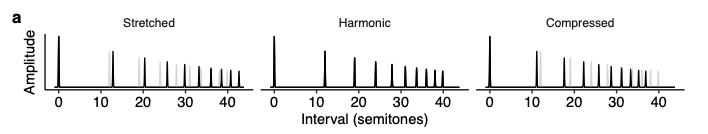

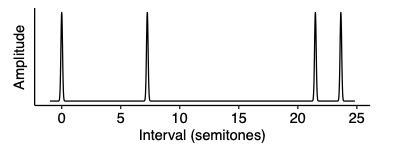

First – by compressing or stretching the harmonic partials as shown below in order to learn how these manipulations affected the perception of pleasantness of the listeners:

Intuitively, this can be understood from the observation that interference is minimized when partials from different tones align neatly with each other (as in the harmonic sequence above). If we then stretch each tone’s spectrum, we must also stretch the intervals between the tones to maintain this alignment, meaning that the fundamental will stray from pure Pythagorean harmonics. Once the individual tones become inharmonic, the overall chord also becomes inharmonic, irrespective of the intervals between the tones.

The result therefore provides evidence that interference between partials is an important contributor to consonance perception.

The metallophones of Indonesian gamelans and the xylophone-like renats used in Thai classical music – each instrument has an idiosyncratic spectrum that reflects its particular physical construction, with potentially interesting implications for consonance perception. The study investigated an inharmonic tone inspired by one such instrument, the bonang, which uses the slendro scale.

The inharmonic slendro scale might be explained in terms of the consonance profile produced by combining a harmonic complex tone with a bonang tone.

The stretching/compressing manipulation is interesting from a modeling perspective, because it clearly dissociates the predictions of the interference and the harmonicity models (partials in defining pleasantness and unpleasantness is called “harmonicity”). It shows that only the former are compatible with the resultant scales. The latter manipulation is interesting from a cultural evolution perspective, because it supports the hypothesis that the slendro scale developed in part as a specific consequence of the acoustic properties of Javanese gamelan instruments.

The study found that manipulating the frequencies of the harmonics can induce inharmonic consonance profiles. If we stretch or compress this partial, we also have to stretch/compress the distance between the two tones in order to hear a pleasant harmony.

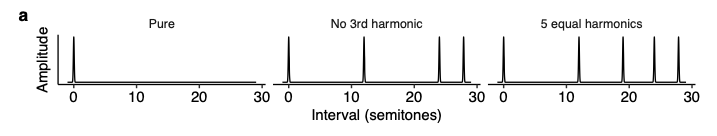

The second step is to enhance or cancel the harmonics in order to understand the role that these harmonics have in our judgment. First, the study considered how consonance profiles may be affected by changing the amplitudes of their tones’ harmonics. In particular, we focus on the so-called spectral roll-off parameter, which determines the rate at which harmonic amplitude rolls off (decreases) as harmonic numbers increase, by increasing the harmonic component:

The study determined no clear effect on pleasantness variability; the profiles remain highly differentiated for all roll-off levels.

Finally, they tested whether consonance profiles are affected by a more radical manipulation by completely deleting particular harmonics:

Removing the harmonicity of the tones in fact reduces the straying away of the pitches from natural harmony.

In summary, the results point to an important contribution of harmonicity to consonance perception. It becomes clear that the upper harmonics of a tone has an important role in defining pleasantness in dyad intervals.

These results provide an empirical foundation for the idea that cultural variation in scale systems might in part be driven by the spectral properties of the musical instruments used by these different cultures. In Western culture, when the reference point is generally based on string instruments, the harmonic tone relationships are different than the ones from South East Asia. In Java, for example, tone relationships are based on Bonang – a collection of small gongs from the Gamelan ensemble, which have a very different series of harmonics or harmonicity, therefore ending up with very different scales used by both Western and South Asian cultures.

The Javanese slendro scale and the pelog scale, both of which are pentatonic, deviate considerably from the Western 12-tone scale.

On the other hand, it is interesting to know that this differentiation is not anthropomorphic: a Westerner listening to Bonang instruments would come to the same conclusion as a South East Asian listener regarding the pleasantness of an interval, and vice-versa. It is indeed the instrument and their specific harmonicity that defines the scale chosen.

So there you have it – the first study found universal relationships between song and spoken words; the second found a locality in the judging of pleasantness in harmonic relationships between tones, although this difference is environmental, not fundamental.

I hope that this will help us understand that in the end, we are the same and our similarities are more than our differences.